Critical Review of Wole Soyinkas Death and the Kings Horseman

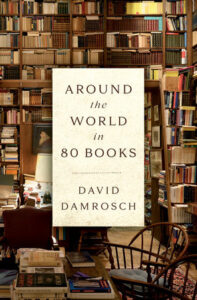

In 1961, a quarter century before he became Africa'south starting time winner of a Nobel Prize for literature, a young Wole Soyinka performed in a radio play version of Things Autumn Autonomously. A twelvemonth later, he attended the briefing at Makerere University College in Uganda where Achebe gave his address on the African writer and the English language. In Death and the King's Horseman (1975), Soyinka brings many of Achebe's themes to the stage, developing them for the chop-chop globalizing postcolonial world of the 1970s. The play'southward global footprint is increasing today in a newly expanding mediascape. A Netflix flick version of the play was appear in June 2020, together with a series based on a Nigerian woman's debut novel. In a news release about the product, Soyinka was quoted equally expressing his pleasance that the producer is a adult female: "In a creative industry which, even in pioneering countries, is so male person dominated, information technology is e'er a please to see robust challenges offered by the female gender, and of ascertainable quality. Mo Abudu'south incursion into this loonshit as motion-picture show and tv set producer has been especially stimulating. Information technology becomes part of i'southward sense of achievement, if one has contributed, however minutely, to the cosmos of an enabling environment." Like Things Fall Apart, Soyinka'south play centers on a powerful but flawed hero who comes into conflict with a colonial administration hostile to local religious customs, and the hero'south patriarchal obsessions run counter to the perspectives of the women around him. The play likewise dramatizes a clash of generations as well every bit of cultures, hinging on a son's shocking death. Yet Expiry and the King'due south Horseman combines many different literary strands, and it is based on an actual issue. In 1946, when a Yoruba king died, the king's companion and counselor Elesin, known as the Horseman of the King, prepared to commit suicide equally allowable by tradition, in order to accompany his male monarch into the afterlife. Nigeria was still a British colony, and the colonial Commune Officer placed Elesin under abort in order to forbid the ritual suicide from taking place. This act of mercy backfired when Elesin'due south eldest son committed suicide in his male parent's place. A friend of Soyinka, Duro Ladipo, had already written a play on this theme in Yoruba under the title Oba Waja, "The King Is Dead." This short, polemical play unambiguously blames the tragedy on the English language imperialists who take denied Elesin his proper part in the immemorial social and cosmic order. As he laments in sexualized linguistic communication, "My charms were rendered impotent / Past the European; / My medicines have gone dried in their calabash." Soyinka developed a far more complex play, drawing on traditional Yoruba drama, in which music, song, and trip the light fantastic convey much of a work's pregnant. Soyinka also builds on the traditions of Greek tragedy, with a grouping of market women, led past the feisty Iyaloja, serving as his version of a Greek chorus. Two years before, Soyinka had published an adaptation of Euripides, The Bacchae: A Communion Rite, in which he boldly associated Greek tragedy and Christian sacrifice: the vehement apart of Male monarch Pentheus by the ecstatic Bacchantes becomes a version of the sacrament of communion. Soyinka's Elesin has much in common with Sophocles' Oedipus. Both are faced with the demand to carry through an ancestral blueprint that other characters—Oedipus's wife, Jocasta, Commune Officer Pilkings in Soyinka—wish to relegate to aboriginal history. In both plays, the life of the customs requires the hero'due south self-sacrifice. Death and the King'due south Horseman also ends with a Sophoclean combination of reversal and recognition, complete with dialogue apropos vision and blindness. Elesin's son Olunde is deeply disappointed when he discovers that his father hasn't committed suicide as he should take. Elesin reacts to Olunde's palpable disgust by crying, "Oh son, don't allow the sight of your begetter plow you bullheaded!" The son's blinding insight into his male parent's failure is doubled with the begetter's reciprocal, devastating vision of his son'southward success, when Olunde'southward torso is displayed to him in the final scene. Soyinka's play tin can too be compared to Shakespeare's tragedies. Unable to free himself from earthly attachments, Elesin has delayed his suicide in order to consummate a concluding-minute marriage, much as King Lear tries to retain a sizeable retinue even after giving the kingdom over to his three daughters. Echoes of Hamlet tin exist heard every bit well. Soyinka has Olunde returning from medical school in England—a modern equivalent to Village's philosophy studies in Germany—to effort to heal the murderous disorder he finds at habitation. Like the young Hamlet, Olunde loses his own life in the process. Soyinka takes further Conrad's overlaying of Africa and England. In Center of Darkness Marlow connects the Congo River and the Thames; at present, one of the market women asks: "Is information technology not the aforementioned ocean that washes this land and the white man'due south land?" Soyinka complicates the theme of the intertwining of civilization and barbarism by shifting the story from its occurrence in 1946 dorsum into the midst of World State of war II. When Jane expresses her horror at the prospect of Elesin's ritual suicide, Olunde retorts, "Is that worse than mass suicide? Mrs. Pilkings, what exercise y'all call what those young men are sent to exercise by their generals in this state of war?" Like Things Fall Apart, Soyinka'due south play portrays the tragedy of a customs struggling to uphold its traditions in the face of colonial domination. Yet Nigeria's situation in 1975 was very dissimilar from 1958, when Achebe was writing on the cusp of independence. A parliamentary authorities was established in 1960, but information technology was overthrown in a war machine insurrection in 1966, and growing ethnic and economic conflicts led to the Nigerian–Biafran ceremonious war of 1967–lxx. Soyinka suffered two years of imprisonment on charges of aiding the Biafran crusade, then went into exile in England, where he wrote his play. Though Soyinka set the action dorsum in the colonial menstruation, Elesin'southward attempt to satisfy his personal desires by evoking traditional customs echoes comparable efforts by Nigeria'south military machine leaders in the 1970s—a similarity we'll meet in Georges Ngal's piece of work as well. Edifice on Achebe's telephone call for African writers to reinvent the English language, Soyinka uses English as both a resources and a weapon. Pilkings and his fellow administrators use blunt language with their African subordinates, who ofttimes speak in a creolized English ("Mista Pirinkin, sir") that registers their lower condition in the colonial hierarchy. But Soyinka plays with the politics of language amongst his African characters as well. When the Nigerian Sergeant Amusa goes to abort Elesin to prevent his suicide, the market place women block his path. After mocking him sexually, they take on British accents: "What a cheek! What impertinence!" They and then stage a piffling play within the play, interim the roles of self-satisfied colonialists: "I have a rather true-blue ox called Amusa"; "Never known a native to tell the truth." Amusa is reduced to a stammering pidgin: "Nosotros dey become now, only make you no say we no warn you." Yet even though he is working for the colonists, Amusa retains a deep-seated respect for his culture's traditional values, and he is horrified when Pilkings and his wife, Jane, don Yoruba egungun costumes for a costume ball. The egungun are the spirits of the dead, full of uncanny power. Amusa pleads with Pilkings, "I beg y'all sir, what yous retrieve you exercise with that clothes? It belong to dead cult, not for human being." Pilkings only mocks Amusa for giving credence to such "mumbo-jumbo." The position of Jane Pilkings is especially interesting in this war of races, genders, and words. Though she is loyal to her frequently obtuse husband, she makes genuine efforts to understand what's really going on, and she gradually becomes aware of parallels between the natives and herself as a woman within a patriarchal guild. Equally she and Pilkings prepare to head off to the costume ball, hearing the ominous audio of drumming in the distance, she hints that he may non take been treatment the problem of Elesin "with your usual brilliance—to begin with that is." Pilkings impatiently replies: "Shut up adult female and get your things on," to which she responds in the language of a native servant: "Alright dominate, coming." _______________________________________ From Effectually the World in 80 Books by DavidDamrosch, to exist published by Penguin Printing, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random Business firm, LLC. Copyright © 2021 byDavidDamrosch.

hodgkinsonforit1992.blogspot.com

Source: https://lithub.com/on-wole-soyinkas-death-and-the-kings-horseman/

0 Response to "Critical Review of Wole Soyinkas Death and the Kings Horseman"

Post a Comment